TOLEDO, Ohio — The ravages of the Spanish Flu epidemic came slowly to Toledo. It had been ravaging Europe and cities on the east coast of the United States, but the Midwest hadn't seen many cases until September.

The news of the day was generally focused on the war in Europe.

So little notice was paid to the occasional stories in September of 1918 about the Spanish influenza starting to infect soldiers and sailors in U.S. military camps; facilities that would later prove to be the fertile epicenters for the spread of the flu.

Toledo gets the warning

In Toledo, by the middle of September, HC Waggoner Toledo's Health Commissioner, issued his first warning that influenza may be coming to Toledo. In the statement, he said there were no cases or any deaths from the flu in Toledo, but residents should take precautions.

The report in the News Bee said it is "very contagious" and comes on rapidly with headaches, chills, coughs, and general aches and pains."

People were advised to avoid crowds, wash their hands, and doctors should report cases to the health department so they could keep a record of them.

Two weeks later, a headline in the Toledo News Bee stated, "The Spanish Influenza Hits Toledo." Waggoner said there are now "hundreds of cases in Toledo". That was on September 30, 1918.

Avoiding the flu

More guidelines were published for the public to follow to avoid getting the flu.

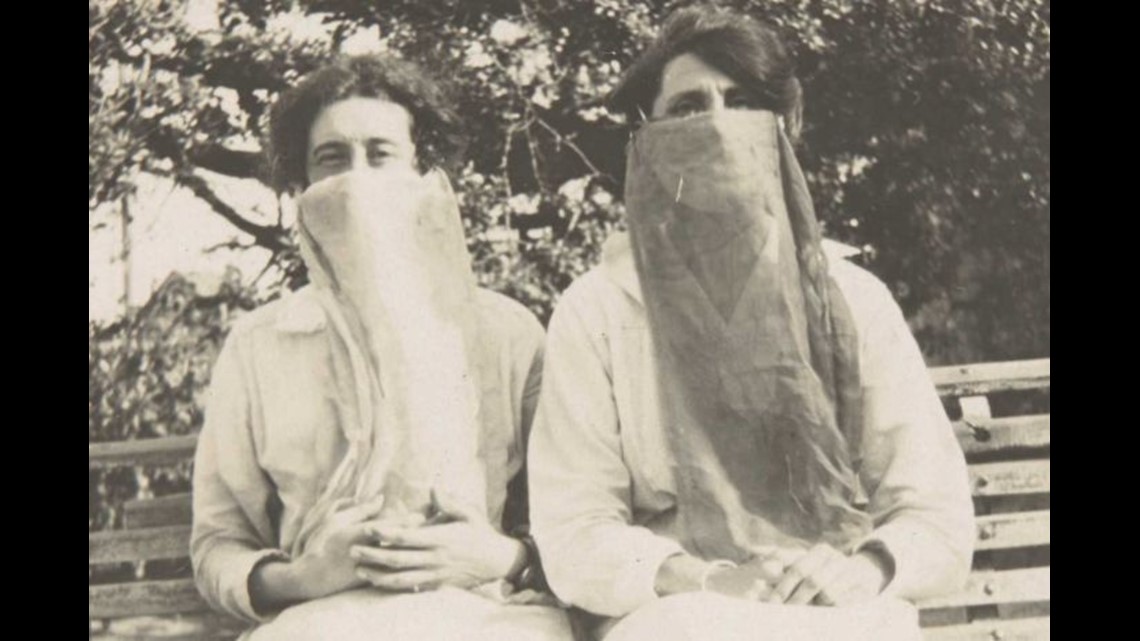

Some doctors at area hospitals started wearing masks when dealing with patients and Toledo schools were dispatching doctors and nurses to check students for symptoms. They were also dispatched to go to houses where children did not show up for school to check them at home.

The streets of Toledo, however, seemed unaffected by these first warning shots of danger. People were still going about their normal activities. Stores were still open. The sidewalks in downtown Toledo were full of shoppers and workers. Social distancing was hardly a concern for most as movie theaters remained open along with lodges, race tracks, churches and schools.

"No reason to be alarmed"

The social indifference of Toledoans might have been coaxed somewhat by Toledo Mayor Cornell Schrieber who made it very clear he didn't think this epidemic was all that bad.

There "no need for alarm" as he was quoted in the newspapers. He and the Health Commissioner Waggoner thought this would just be another mild strain of the usual annual flu and would not be deadly.

Unlike other cities in Ohio and the Midwest, he did not implement any bans or shutdowns of the city immediately.

The facts however were in conflict with the mayor's opinion. Deaths from the flu were starting to be noted in the Toledo NewsBee and the Toledo Blade.

At home and elsewhere, news of Toledo soldiers and sailors dying from the flu became more frequent. For example, Harry Smith, a 29-year-old Toledo policeman, on leave from the police department and serving his country in France died there from the flu and pneumonia.

Another story in September revealed that Charles Lawrence, from North Baltimore, never made it past the Naval Training Center in Chicago when he was stricken with the flu. His body was shipped home for the funeral. Their stories were not unique.

Toledo gets locked down

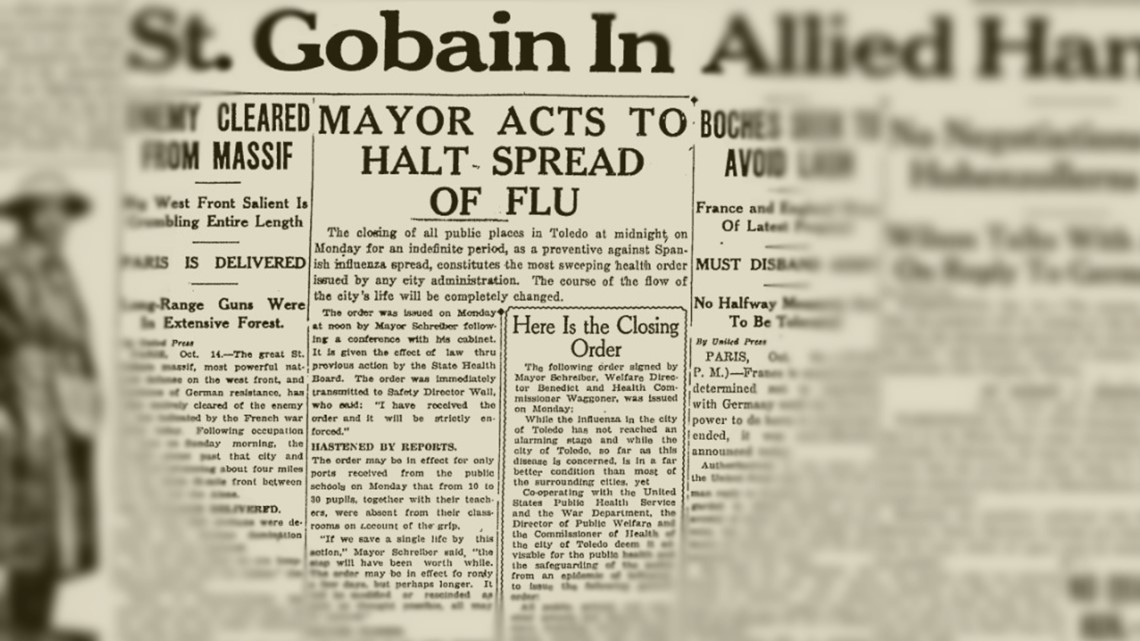

Finally, by October 13, Toledo Mayor Schreiber got word from the state of Ohio health authorities that he needed to take action in Toledo. He did so quickly. His first action was to close down a planned Liberty Loan rally and parade at the courthouse.

Stores had their hours shortened, large gatherings of people were banned, schools were shut down, saloons were shuttered (although 400 saloon owners fought for reopening), church services were canceled, the library was closed and the beloved movie houses throughout town went dark.

Life came to a relative standstill by the middle of October 1918. Not unlike what Toledoans and the rest of the country are experiencing today. Even in 1918, epidemiologists knew that without a vaccine, keeping people apart was the most effective way to stop the spread of the virus.

Toledo hospitals began banning visitors as doctors and nurses understood what could happen if they and their patients were not protected. And as patients filled the beds of St. Vincent and Flower and Toledo hospitals, there was a need for volunteer nurses to help out in the crisis.

A call went out to summon those interested in lending some time and compassion. While many people who had the illness were taken to the hospital, there were thousands of others who had to be quarantined because of exposure and while largely unreported, Toledo Health Department records showed that over 8,000 homes in the city had been put under quarantine.

The mayor had put the Red Cross in charge of handling most of the operational and medical logistics of handling the epidemic.

The news treatment was low key

Surprisingly, the newspapers in Toledo did not pay as much attention to the situation as you may imagine. No banner headlines, and rarely was it placed prominently on the front page.

In the Toledo News Bee, the stories were often buried somewhere in the middle of the paper, in the middle of the page. A rather curious observation, given the significant impact the flu was having on the city.

Mayor Schreiber also tried to downplay the epidemic. He kept insisting that it would be over soon and wasn't cause for alarm. He was eager to get the city reopened, but said he would follow the lead of the state health department.

Meanwhile, in the rural areas outside of Toledo, there was no ban, per se, and many Toledoans were just leaving town to get a drink, go to a meeting or party. County commissioners refused to order a ban on the "slackers" and the flu was able to spread into those rural townships which also saw a spike in the caseloads.

At this point, in 1918, the long war in Europe against the Kaiser forces was in its final month. Americans were keeping watch on the war news, but hard to do without reading the stories of the American Yanks who were not only being shot at in the trenches, but also having to deal with the deadly threat of the Spanish Flu. And it was a most lethal enemy, perhaps more frightening than the Germans. The flu was killing more American soldiers than were German bullets and bombs.

Flu deadly to area military

Many of the American service members never made it home from training camp as places like Camp Sherman in Ohio became one of the "hot zones" and one of the deadliest military camps in the country.

Many Toledo area recruits who reported to Camp Sherman arrived back home at Union Station in coffins.

At its peak, a number of Toledo nurses were sent to Chillicothe to help heal the sick. Some of them, too, were killed by the same disease.

One of them was Margaret Kuhlman of Toledo who went to the camp in the middle of October, only to die from flu herself just 10 days later. She had just graduated from Toledo Hospital's nursing program and enrolled with the Red Cross for war duty.

Another tragic story from Camp Sherman involved Fred Yeager of Perrysburg who died from influenza at the camp in October.

Upon hearing the news, his grandmother died of shock. Both were buried at Ft. Meigs Cemetery in Perrysburg.

Death toll mounts

The mounting death toll was more than a number. Each was a person, a family, a dark story.

In one tiny sad note in the Toledo News Bee, 25-year-old Jessie Wilson, a burlesque dancer who was doing a revue in Toledo called "The Social Maids" became stranded in the city when the theater shut down. She, like many showgirls at the time, stayed at the Navarre Hotel. While she was there, she contracted typhoid fever and died.

The article says the young woman had no home, so a collection was taken at the hotel among the guests, and Jessie was buried at Calvary Cemetery.

There were many other stories, and it's likely that given the number of deaths, there are few families in the Toledo area who were not touched one way or another by the epidemic of 1918.

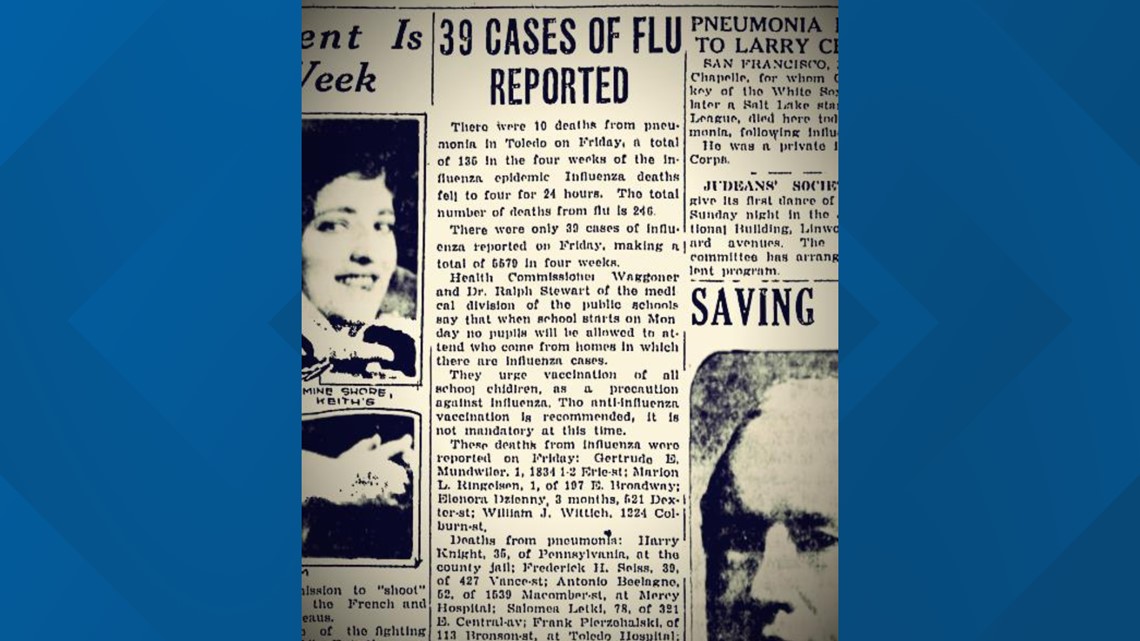

In November, health experts said they believed the epidemic had peaked and was starting to abate. Following state guidelines, Mayor Schreiber ordered a partial lifting of the ban.

Store hours were extended and church services were allowed to be held.

Theaters could reopen and meetings at the many lodges and fraternal groups in Toledo were given the green light.

There was hope

By November 11, the hope turned jubilant on the war front as Germany surrendered and fell to defeat.

In Toledo, people were compelled to party together for the first time in many weeks and that day saw throngs of people turn out into the downtown streets for a night of revelry.

With the close of the war, there was also optimism that the city could close the book on the Spanish Flu epidemic. People were eager to resume life.

When the city’s entertainment venues did finally open their doors, large crowds were there with cash to spend. Theater seats were filled and saloons had drinkers crowding the bar before breakfast.

The end almost near

While most businesses and activities were released from restrictions, the virus showed no sign of leaving. The grim toll of people becoming ill and dying did not stop.

One day after the ban was fully lifted in November, the death toll for the next two days was 19 in the city of Toledo. The flu stubbornly lingered.

In December, with the schools open again, the influenza returned and with some cases of Diptheria to contend with, the absentee records revealed 5,000 students out of 32,000 were calling in sick. Toledo schools were closed again through the end of the month.

Children under 18 were banned from movie houses, art museums, parties and all forms of public gatherings. It was urged that parents leave their children at home while shopping, as children were not allowed in the stores.

When the children were finally allowed back in school and the restrictions lifted, January and February saw a reduced number of flu cases and death. By the end of February, the numbers seemed to return to what would be considered normal.

It is estimated, however, that from September through February, at least 10,000 took ill with the flu in Toledo. Some estimates say it might have been as many as 20,000. As for deaths in Toledo, 716 is the official death toll from either the flu or the flu-induced pneumonia. Counting the area around Toledo, the number was likely to exceed 1,000.

A large number, but deaths per capita, much better than many other cities in Ohio, which had a death toll of over 17,000 people for the period of September 1918 to February 1919.

In many ways, the battle against Spanish Flu is strangely similar to what is being experienced with the current coronavirus pandemic. It may not be exact, but certainly parallels and lessons can be drawn. As the old maxim goes, "the past may not repeat itself, but it rhymes".